The Heiligenberg – view across the Neckar River – Heidelberg.

The Heiligenberg

Forest and landscape

Today, the Heiligenberg is a green, wooded hilltop. Until the mountain was settled by humans in the Bronze Age, beech and oak trees grew here. The inhabitants on and around the mountain used the wood without a thought for future generations and as a result remained barren and almost treeless for centuries. From a forestry condition report: “Only hedges and shrubs, no usable wood”.

It was not until the beginning of the 19th century that re-forestation began and the forest was managed sustainably. The forest paths that visitors find today have only existed since the middle of the 19th century. Before that, there were almost only so-called grind paths or sunken paths. At the beginning of the 20th century, an infrastructure was developed for the use of the forest as a recreational area. Footpaths were created, huts and wells were built, signposts were erected, viewing points were created, and much more besides. In line with today’s requirements, is constantly being expanded with: signs and information boards, car parks, marked trails for hikers and special mountain bike trails have been set up.

Heiligenberg – History

The Heiligenberg is not only an important landmark, but also a cultural monument of the highest order. Its outstanding natural protective location with a clearly defined summit area and its dominant position in the landscape attracted people very early on, leading to the establishment of a large settlement as early as the Bronze Age. Since the 5th century BC, the mountain has played a special role in the eventful history of the region. At first glance, two monastery ruins and a monumental open-air stage reveal only the most recent relics of its millennia-long history of settlement. In contrast, the two concentric enclosure walls from the Celtic period are now, at best, recognizable above ground as stone-strewn terrace edges. The fortification consists of an inner wall with a circumference of 2.1 kilometers and an outer wall, located significantly lower down, with a circumference of 3.1 kilometers. Within the ring walls, hundreds of dwellings and pits occupied the plateau and slopes on terraced hillsides.

The Heiligenberg is not only an important landmark, but also a cultural monument of the highest order. Its outstanding natural protective location with a clearly defined summit area and its dominant position in the landscape attracted people very early on, leading to the establishment of a large settlement as early as the Bronze Age. Since the 5th century BC, the mountain has played a special role in the eventful history of the region. At first glance, two monastery ruins and a monumental open-air stage reveal only the most recent relics of its millennia-long history of settlement. In contrast, the two concentric enclosure walls from the Celtic period are now, at best, recognizable above ground as stone-strewn terrace edges. The fortification consists of an inner wall with a circumference of 2.1 kilometers and an outer wall, located significantly lower down, with a circumference of 3.1 kilometers. Within the ring walls, hundreds of dwellings and pits occupied the plateau and slopes on terraced hillsides.

The “Heidelberg Celtic Head” is perhaps the only clear indication of a Celtic prince who probably resided on the Heiligenberg 2,500 years ago and who, after his death, was buried under a mighty burial mound at the foot of the hilltop settlement.

The barren soil allowed only very limited agriculture, which is why the Celts were dependent on the yields of the farmers in the fertile plain. The mining and smelting of iron ore cannot have been the primary source of income for the inhabitants of the heights, as the quality of the ore deposits was insufficient for this. It was more likely a suspected “control station” for the movement of goods at the so-called Hackteufel, a granite reef in the Neckar River that severely impeded shipping until it was canalized. This prompted the Celts to develop Heiligenberg into a central seat of power. In the 5th and 4th centuries BC, it was the political, religious, and cultural center of the entire surrounding area for about 150 years and only lost its importance in the 3rd century.

In the following period, the mountain had a no less eventful history: after the Celts, the Romans built a summit sanctuary for their gods Jupiter and Mercury. The foundations of one of the temple buildings have been preserved under the impressive ruins of St. Michael’s Monastery, and their layout is marked on the ground today. In the early Middle Ages, there was a fortified royal court here, which is referred to as “Aberinsburg” in sources from the 9th century. Centuries later, monks from Lorsch Monastery made it their “holy” monastery mountain: They built St. Michael’s Monastery on the rear hilltop, followed shortly afterwards by St. Stephen’s Monastery on the front summit. In the centuries that followed, the monastery became a popular place of pilgrimage to the relics of St. Frederick, who died in 1070.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the glory days of the pilgrimage site were numbered, the monastery buildings fell into disrepair, were transferred to the university as part of secularization, and were finally approved for demolition. In 1885, the observation tower was built at St. Stephen’s Monastery. In 1934/1935, the National Socialists created the most recent architectural monument on the mountain with their massive open-air complex “Thingstätte,” which still shapes the appearance of the mountain today.

THE CELTIC HILLTOP SETTLEMENT

The Heiligenberg towers over the Neckar valley at a height of about 330 meters. Deep stream valleys divide it from the Odenwald, which is in the northwest. Only a narrow ridge connects the Heiligenberg with the hilly hinterland. These special terrain conditions on the border of the Rhine plain allow the Heiligenberg to dominate the landscape and provide a safe refuge for all people. This has attracted people for many thousands of years.

The Heiligenberg towers over the Neckar valley at a height of about 330 meters. Deep stream valleys divide it from the Odenwald, which is in the northwest. Only a narrow ridge connects the Heiligenberg with the hilly hinterland. These special terrain conditions on the border of the Rhine plain allow the Heiligenberg to dominate the landscape and provide a safe refuge for all people. This has attracted people for many thousands of years.

A few discoveries from the New Stone Age (6th to 5th millennium BCE) give proof that the Heiligenberg was used for hunting or gathering of wood and berries, before people permanently settled on the summit. More numerous ceramic discoveries of the so-called “urnfield culture” imply that a larger settlement first grew up on the Heiligenberg in the Late Bronze Age (around 1200 BCE). At that time it took on a central position in the dense settlement structure of the Lower Neckar Valley.

The obvious disadvantages of the exposed location of the settlement (harsh climate, less fertile soil, difficult supply of water) weighed less than the protective role. In the 5th century BCE, the Celts built a double circular wall as protection for the main and side summits. Within this wall, nearly the entire area was settled. On an area of 52.62 hectares (approx. 73 soccer pitches) there are traces of over 450 “Wohnpodien”. These hillside terraces were home to houses, granaries and workshops. The only water-bearing spring, the Bittersbrunnen well on the north-western slope of the Heiligenberg, was deliberately included in the weir system to ensure the water supply in an emergency.

( Text from the www.geo-naturpark.de on-site info board. )

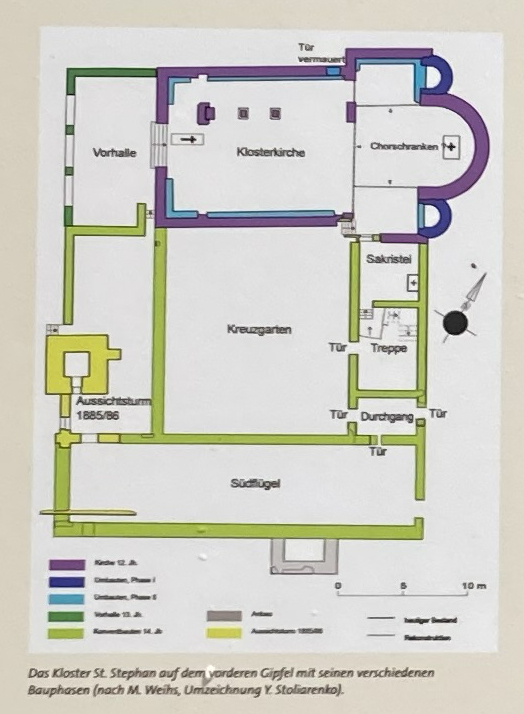

The Monastery of Saint Stefan

Around 1090, the Benedictine monk Arnold founded a chapel on the front summit of the Heiligenberg. Apparently, the small church dedicated to St. Stephen was particularly valued by the monks as a place of prayer, so Abbot Anselm of Lorsch founded a monastery there. St. Stephen’s was endowed with extensive lands to provide for the monks’ livelihood. In 1096, several crusaders entrusted their money to the monk Dietbert for safekeeping before setting off for the Holy Land. When the knights did not return from the crusade, their fortune benefited the expansion of the young monastery.

Noteworthy is the tombstone of a woman named Hazecha, discovered in 1932. The inscription indicates that the widow of the knight Rifrid donated her entire inheritance to St. Stephen’s Monastery around 1100. Her husband, who had co-signed the monastery’s founding document as a witness, had apparently been buried elsewhere. Perhaps he too had set out on the crusade and never returned home.

The three-naved church with transept and three adjoining apses was built in the 12th century. After Premonstratensian monks from All Saints in the Black Forest took over the monastery in the 13th century, it was gradually rebuilt. A vestibule was added to the west of the church. The location of the monks’ living and working quarters from the time of the monastery’s foundation is unknown; the three-winged cloister south of the church was not built until the 14th century. After its dissolution in the 16th century, the monastery fell into disrepair. In 1885/86, the stone material from the ruins was used to build the observation tower.

The Monastery of Saint Michael: Michaelskloster

The Benedictine abbey Lorsch, founded in 764 and promoted to Imperial Monastery in 772, developed rapidly under the protection of the Franconian kings to a religious, political and economic center of power in the region. When Abbot Thiotroch had a church built on the Heiligenberg in 870. tnis occurred certainly with the approval of the king (or at his bidding). The “Aberinesburg”. as it was called, the royal court at the summit – was not donated with all the accompanying propertes and serfs by King Ludwig III to the abbey until the year 882.

The Benedictine abbey Lorsch, founded in 764 and promoted to Imperial Monastery in 772, developed rapidly under the protection of the Franconian kings to a religious, political and economic center of power in the region. When Abbot Thiotroch had a church built on the Heiligenberg in 870. tnis occurred certainly with the approval of the king (or at his bidding). The “Aberinesburg”. as it was called, the royal court at the summit – was not donated with all the accompanying propertes and serfs by King Ludwig III to the abbey until the year 882.

Later on, the church dedicated to the Archangel Michael amassed considerable additional properties due to further donations. This made it possible for Abbot Reginbald of Lorsch to establish a monastery on the Heiligenberg in 1023. The monks, led by a prior, followed the rules of St. Benedict. A large, three-naved basilica with a cloister to the east and an atrium to the west was constructed in several building phases. A saint’s legend concerning the Abbot Friedrich von Hirsau, buried on the Heiligenberg in 1071, made the monastery a popular pilgrimage site.

In the 13th century, the Archbishop of Mainz took over the provost church in Lorsch and populated the monastery around 1265 with monks from the Premonstratensian monastery Allerheiligen in the Black Forest. The monastery decayed visibly starting at the beginning of the 16th century and was completely disbanded during the Reformation (around 1555). The buildings were given to the university, which re-leased them in 1589 for demolition.

Opening hours: – (St.Michaels Monastery & St. Stephen observation tower)

March–September: 10 a.m.–7 p.m.

October–December: 10 a.m.–4:30 p.m.

Closed on Mondays and Tuesdays!

Closed in January and February, as well as on Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve.

Thingstätte

Thingstätte

Thingstätte The Thingstätte is an open-air amphitheater built in 1934/35 by the “Reich” Labor Service and Heidelberg students. Its semicircular auditorium offers seating for 8,000 and standing room for 20,000 spectators and is reminiscent of ancient Greek theaters. It was part of the National Socialist “Thing movement” and was intended to be used for propaganda events, but was only in use for a few years. Today it is a listed building.

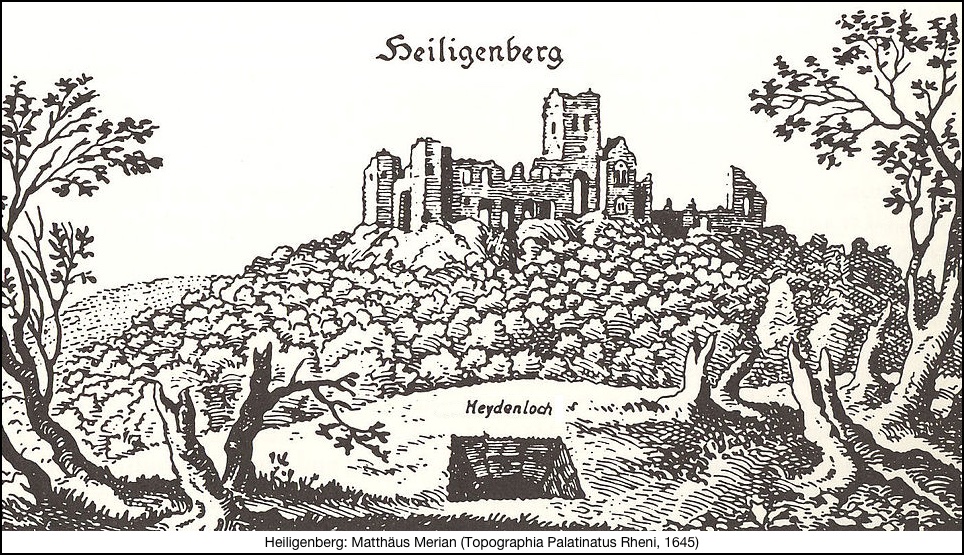

The ruins of St. Michael’s Monastery on the Heiligenberg with the brick-built water drawhole of the Heidenloch.

The ruins of St. Michael’s Monastery on the Heiligenberg with the brick-built water drawhole of the Heidenloch.

Charles de Graimberg, 1774-1864, pen and ink, brush wash, Kurpfälzisches Museum Heidelberg, Inv. No. Z 757, photo: KMH (K. Gattner)

The mysterious Heidenloch

Another remnant of human activity – the Heidenloch (heathen hole).

The Heidenloch has always fascinated locals and visitors alike. Legends and myths have surrounded the underground shaft for centuries. It was believed to have been created by pre-Christian pagans, who dug a hole in the mountain where Satan sat and proclaimed his false prophecies.

The Heidenloch has always fascinated locals and visitors alike. Legends and myths have surrounded the underground shaft for centuries. It was believed to have been created by pre-Christian pagans, who dug a hole in the mountain where Satan sat and proclaimed his false prophecies.

Around 1600, geographer Matthis Quad described the impressive shaft as a vital well, but also told of a brother of St. James who had descended into the Heidenloch twice and seen fantastic things there. He said that deep down there was a room with two doors, in which stood two treasure chests, each guarded by a chained dog with fiery eyes. Finally, around 1840, the French poet Victor Hugo paid a night-time visit to the Heidenloch and reported hearing a ghostly voice nearby. He suspected that the eerie hole was the empty grave of a giant, perhaps also a druid’s chamber or the shaft of a Roman camp, the water basin of a vanished Byzantine monastery, or even the bone cellar of a destroyed gallows.

To this day, the Heidenloch continues to capture the imagination. In 1999, Martin Schemm published his fantastical-mythological novel of the same name. In it, mysterious beings emerge from the Heidenloch in the summer of 1907, spreading fear and terror, and even causing deaths. Once again—and certainly not for the last time—the mysterious Heidenloch is at the center of eerie encounters.

Facts and figures about the Heidenloch

The Heidenloch is a mighty shaft measuring around two to three meters in diameter, which was driven 56 meters deep into the sandstone of the mountain. A well casing 2,10 meters high was installed in the lowest part, the blocks of which were recovered and have now been rebuilt in the Kurpfälzisches Museum. The well was fed by water seeping from the surrounding rock. For a long time, there was controversy about who dug the shaft and why they undertook this enormous technical feat.

Today, the Heidenloch facility is dated to the first half of the 12th century, when the recently founded St. Stephen’s Monastery nearby needed to be supplied with water. However, the facility was so unproductive that it was abandoned very soon and gradually filled almost completely with rubble, smashed building components, and ecclesiastical and secular household goods.

In 1936 and again in 1987, the shaft was systematically cleared by the Kurpfälzisches Museum. During this process, the excavators also recovered clay pots from around 1400, parts of tiled stoves, and medieval weapons. The finds prove that at the end of the 14th/beginning of the 15th century, warfare must have taken place in St. Stephen’s Monastery, the traces of which were then “disposed of” in the Heidenloch.

You Tube – Film expedition into the depths: by the Kurpfälzisches Museum Heidelberg (German language)