Charles de Graimberg

Excerpt from: HEIDELBERG: ITS PRINCES AND ITS PALACES

(Pages 342 – 343) by ELIZABETH GODFREY (pseudonym of Jessie Bedford (1853–1918))

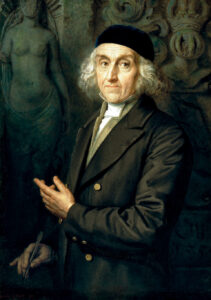

Charles Francois de Graimberg (1774 – 1864) in a portrait by Guido Schmitt, 1902 © Kurpfälzisches Museum Heidelberg

” . .. . Nor must we forget the man to whose quiet and unostentatious work antiquarians owe a deep debt of gratitude. Three great gifts the nineteenth century brought to Heidelberg: the restoration of its University, the return in 1814 of its Library from its long sojourn in the Vatican, and not least the arrival of Count Charles de Graimberg just in time to save the Castle ruins from utter demolition. Neglect and ivy had done their worst, tourists chipping off bits of carving to carry away were doing the rest; another century would have seen little but crumbling walls but for this Frenchman belonging to a family of Emigres from Chateau de Paars. Coming on a mere visit of curiosity, with the object of sketching in a picturesque neighbourhood, he fell forthwith so completely under the spell of the place that he never left it again, but devoted his long life, all his money, his zeal, and devotion to rescuing it from decay and depredation, to searching its records, collecting its scattered treasures, patiently making an indifferent people and a callous government realize the treasure they were suffering to slip away.”

First he took rooms above the Well-House, whence he could pounce out upon mischief-working tourists, and where he began to collect coins, prints, broken pieces of sculpture, anything, in fact, that could throw light upon the past, all the while making pencil sketches and studies of the ruins, which he had engraved and sold in Paris, with the twofold purpose of earning money for the work and arousing interest in the subject. He was allowed to hire rooms over the Gate-House and subsequently in the domestic buildings to house his growing collection, but as it was not safe from depredation he had to appoint a caretaker at his own expense. Not until 1849 did the government allow him rooms in the Friedrich Bau, over the chapel, for what has now grown into the Castle Museum, and become one of the most interesting sights of the place. He had offers from other countries, one from England, to purchase his collection, but he would not suffer it to depart. Had the State bought it, it would have been lost to Heidelberg, as it would most likely have been taken to Karlsruhe or Mannheim.

His only helper was Dr. Thomas Alfried Leger, one of the professors, who was like-minded with himself in his devotion to the old place and its traditions, and wrote a most interesting historical guide, which De Graimberg edited in 1860 with Herr Barth’s illustrations. Up to extreme old age he worked bravely on under every sort of discouragement, lack of means, actual suffering from the cold of the windowless, unheated rooms where he toiled, only laying down his task with his life, which ended in 1864 at the age of eighty. When he was gone the town awoke to his merits and placed a tablet to his memory near the entrance to his museum, acknowledging what they owed to “the stranger who showed himself the noblest of their citizens.”

Charles de Graimberg and his palace on the Kornmarkt

Translation in parts from text by Prof. Dr. Frieder Hepp,

Director of the Kurpfälzisches Museum Heidelberg

150 years ago, on November 10, 1864, at the age of 90, the French emigrant Count Charles de Graimberg died in his palace on Heidelberg’s Kornmarkt. He spent more than half of his life in the Neckarstadt. Even today, an impressive portrait by the painter Guido Schmitt (1834-1922) still bears witness to Graimberg’s special connection to his adopted home. It shows a distinguished man in front of the entrance portal of the Ottheinrich Building, one of the most striking parts of Heidelberg Castle. Graimberg refers to this Renaissance palace, which is also a clear expression of his commitment to saving the castle ruins, a project that was one of the great achievements of his eventful life. So let’s take a look back.

150 years ago, on November 10, 1864, at the age of 90, the French emigrant Count Charles de Graimberg died in his palace on Heidelberg’s Kornmarkt. He spent more than half of his life in the Neckarstadt. Even today, an impressive portrait by the painter Guido Schmitt (1834-1922) still bears witness to Graimberg’s special connection to his adopted home. It shows a distinguished man in front of the entrance portal of the Ottheinrich Building, one of the most striking parts of Heidelberg Castle. Graimberg refers to this Renaissance palace, which is also a clear expression of his commitment to saving the castle ruins, a project that was one of the great achievements of his eventful life. So let’s take a look back.

Charles François de Graimberg was born in 1774 on the Paars estate near Chateau Thierry in Champagne, the second son of Count Gilles François de Graimberg and his wife Anne le Moigne de Roeuve. From the age of 13, he attended the military school run by Benedictines in Rebais. After the outbreak of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Jacobin reign of terror, the family emigrated to Germany in 1791. The 17-year-old Graimberg then fought as a volunteer, first in a French émigré regiment, then in English pay against the revolutionary army. He was promoted to officer, but retired to the English Channel Island of Guernsey in 1796, where he remained until 1805, working as a tutor and devoting himself to improving his painting and drawing skills.

1810: Charles de Graimberg visits Heidelberg for the first time

The artist, who was also a collector, visited Heidelberg for the first time on October 4, 1810, where “some old Palatinate coins that de Graimberg found in Heidelberg Castle” are said to have prompted him to become involved in the preservation of the castle ruins, which had been degraded to a quarry, and to assemble a collection of Palatinate art and cultural objects using his own fortune. No wonder that Graimberg’s first domicile in the gate tower of the Transparent Hall Building and in the Brückenhaus at the entrance to Heidelberg Castle soon became too small and he had to look for new living quarters and exhibition space. In addition, in 1823, the now 49-year-old had married Polyxenia von Perglas (1769-1844), the daughter of Baron Leopold Pergler von Perglas, who was 22 years his junior. Together, the couple acquired a house at Hauptstrasse 107, but the family, which was now made up of seven members, needed even more space. Graimberg therefore bought the property on Kornmarkt from the Schönau estate in 1839, here he was able to house his art collection as well as his engraving business.

The palace itself was first mentioned in documents in 1713. It is located at the south-east corner of the Kornmarkt between Burgweg to the west, Karlstraße to the north and Kanzleigasse to the east. Today it presents itself as a two-storey, almost regular four-winged building with a large hipped roof, an inner courtyard and a fountain. Originally, the estate probably consisted of two residential buildings. The first owner was the court chamber deputy director Johann Weyler. He acquired parts of the “freyadelichen” property from the community of heirs of Paul von Rammingen, who served in the Thirty Years’ War as an envoy of the later Elector Karl Ludwig in Paris, among other things, represented his interests in Paris. Weyler built a residential building facing Kanzleigasse. Before 1743, an extension with a front building facing Kornmarkt.

The Palais becomes a school building

Various scientific studies provide detailed information information on the further history of the property. It is assumed, for example, that in 1792 the corner house including the garden, was sold to the Churpfalz clerical administrator Wilhelm Heinrich Bettinger. It is also said that the estate was already divided between Bettinger and the Schönau estate at this time. However, it was not until 1818 that the Baden Reformed Church is mentioned by name in documents as the purchaser. The church then set up a “reformed schoolhouse” in the complex, where lessons were held between 1823 and 1839. Graimberg had the former schoolhouse refurbished for his needs after the purchase. 13 rooms on the first floor, including the former chapel, and parts of the upper floor were used to display the collection. To draw visitors’ attention, the two arched windows were decorated with wooden tracery and above them a new balcony balustrade at the north-west corner facing the towards the Kornmarkt.

One year after the purchase, the so-called “Particulier” Charles de Graimberg received the Heidelberg citizenship and thus also became a citizen of Baden. In 1842, he was able to open his “Antiquities Hall of the Heidelberg Castle”, at least in part. A year later, Graimberg was still complaining about the fact that “the newly built hall” could not yet be used for the presentation, as there was “some influence of moisture”. In addition to the collection and the family, Graimberg also moved his publishing house on the ground floor. To finance his business he set up a sales room for his now famous engravings, which he sold to the many tourists who came to the castle. The representative rooms from the late 18th century on the upper floor of the north wing Graimberg left unchanged.

Charles de Graimberg.’s special cultural significance for Heidelberg lies in his capacity as a collector of all kinds of works of art relating to the history of the Electoral Palatinate and southwest Germany: Paintings and graphic testimonies with portraits of members of the princely house and its court, of artists, advisors and officials in his service, as well as depictions of events, sculptures (such as the Windsheim Twelve Messengers Altarpiece by Tilmann Riemenschneider, which he bought at auction from the Martinengo Collection in Würzburg in 1861), decorative arts, medals, coins, porcelain and other objects from this area. Graimberg initially housed these works of art as a “hall of antiquities” in the Torbau, later in the Gläserner Saalbau and Friedrichsbau of the palace, and occasionally in museum-like rooms in his corner house on the Kornmarkt in Heidelberg. After his death, most of it was acquired by the Heidelberg city council (1879) and today forms the basis of the Kurpfälzisches Museum, which has been housed in a baroque palace on Hauptstraße since 1907.

1864: Graimberg dies

After Graimberg’s death in 1864, the community of heirs sold the house to his son Philibert. At the same time, the lawyer Albert Mays, who was interested in history, campaigned for the preservation of the collection and in 1879, after parts of it had already been sold, managed to have it purchased by the city of Heidelberg with the help of the painter Wilhelm Trübner. To house the collection the city acquired the representative baroque palace of law professor Philipp Morass, built in 1712, Palais Morass at Hauptstraße 97 and in 1906 and in 1908 opened the “Städtische Kunst- und Alterthümersammlung zur Geschichte Heidelbergs und der Kurpfalz”, renamed “Kurpfälzisches Museum der Stadt Heidelberg” in 1921.

To this day, the Palais is inextricably linked with the name Charles de Graimberg. The visionary recognized early on the possibility that Heidelberg could become a cultural attraction for an international audience after the fall of the Old Empire in the beginning of the bourgeois age. However, as a member of the nobility and a Catholic Frenchman, he was not without controversy in the Neckar city. In particular, his fight to preserve the castle ruins was often met with incomprehension by parts of the local population and also by the state authorities. However, Graimberg’s idealism did not deter him from putting his firm decision into practice: “to create a worthy recognition abroad for this area, which was still so little known at the time”. The use of his palace and the maintenance and expansion of the art collection he founded are both an incentive and an obligation for the city of Heidelberg in the future.