The Name Heidelberg

The name Heidelberch was first mentioned in a document from the Schönau monastery in 1196. At that time, the village was still owned by the diocese of Worms.

The name Heidelberch was first mentioned in a document from the Schönau monastery in 1196. At that time, the village was still owned by the diocese of Worms.

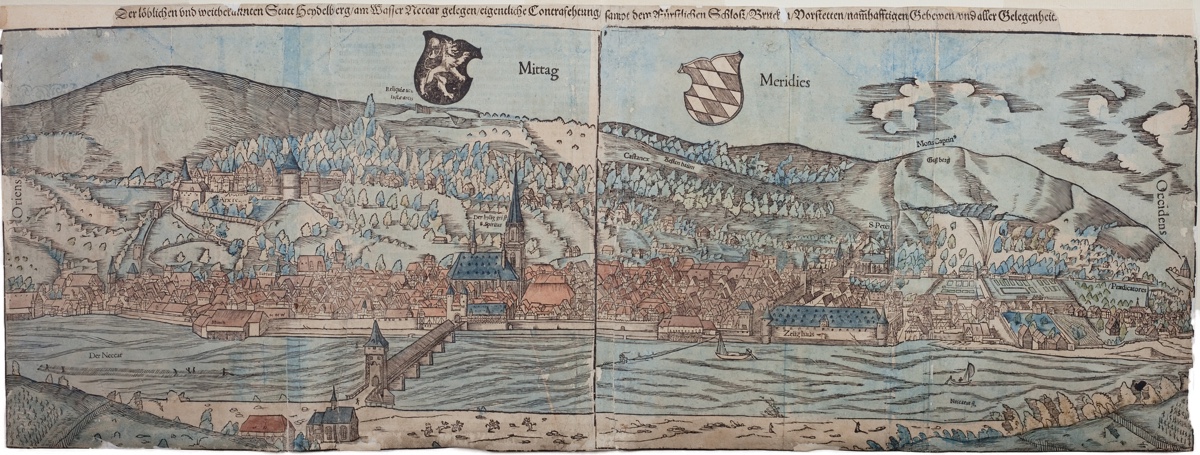

It should also be noted that in times gone by the vegetation on the hills behind the town and castle was very different to the present day with its woods and forests. The illustrations from 1550 and 1620 by Sebastian Münster and Matthaeus Merian are a good indication.

Over the last several hundred years there have been many explanations as to the derivation of the name. The following seem to be the most probable.

“Manual for Travellers to Heidleberg and Its Environs.”

Third Edition – Helmina von Chézy

“The castle probably derives its name from the bilberries (Heidelbeeren), which grow in great abundance on that height: hence it was called: the palace on the Heidelberg, which was transferred by degrees to the habitations situated in the valley, underneath the castle, form the present town, which was already in the middle of the 13th century, under Lewis II, connected by two bridges with the opposite shore; a sure sign of the flourishing state of a town that, as the chronicles inform us, has repeatedly been visited by fire and water. The original foundation of the lower castle, whose grand ruins constitute the ornament and glory of Heidelberg; for it is certain that both palaces existed already in 1329. Equally certain it is that both the town and the lower palace were considerably enlarged and beautified under Robert I († 1390) and under Robert II († 1898).”

Excerpt From: Helmina von Chézy. “Manual for Travellers to Heidleberg and Its Environs. Third Edition”.

Heidelberg: J. Engelmann, 1838

Heidelberg – Its princes and its palaces –

Elizabeth Godfrey – 15 February 1853 – 22 May 1918 (aged 65)

Written by Elizabeth Godfrey, which was a pseudonym for Jessie Bedford. Bedford began her literary career through contributions to literary periodicals of the time such as Temple Bar and Macmillan’s Magazine. Bedford wrote many books on seventeenth century England. Her interest in German history was not known until the publication of this work.

Page 19

Conrad von Hohenstaufen –

. . . in 1155 his brother, the Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa, made him Count Palatine and

. . . From his grandfather, Duke Friedrich of Swabia, he inherited the castle on the Lesser Geisberg,

Page 20

Conrad resided sometimes at Staleck, but chiefly made his home in his castle on the hill which began to be called Heidelberg, or the hill of the bilberries, ( Vaccinium myrtillus ) for in olden days instead of being as now richly wooded it was a wild heathy waste. Other derivations exist for the name, but the design on the old banner preserved in the Rath-Haus till the middle of the fifteenth century, and also on a carved stone in the upper fountain in the Bergstadt, bear this out. On a blue shield a hill with bilberry bushes, and on the summit a maiden in white bearing a bunch of bilberries in her right hand.

Pliny mentions a purple dye used by the Franks as being, not the murex, but a vegetable dye, “vaccinium,” supposed to be extracted from the whortleberry or bilberry.

Heidelbeere: Vaccinium myrtillus or European blueberry is a holarctic species of shrub with edible fruit of blue color, known by the common names bilberry, blaeberry, wimberry, and whortleberry. It is more precisely called common bilberry or blue whortleberry to distinguish it from other Vaccinium relatives.

Herkunft von der Heidelbeere? Der Stadtname

Heidelberg: Kleine Stadtgeschichte (German Edition) Oliver Fink

The search for the meaning of the town’s name is just as difficult as the search for its origins. It has been suggested that Heidel is a synonym for buckwheat – a heather. In fact, the earliest views of the town show the heights of the Königstuhl in an unwooded state (to which the second part of the town’s name “berg” almost certainly refers). For a long time very popular, but now considered unlikely, was a possible derivation of the name from the blueberry, which is said to have grown here extensively, but for which there is no sound evidence – the middle syllable “beer” would then have been bracketed in the name, which linguists call the bracket form. A derivation of “Heidenberg” as a reference to the Heiligenberg with its significance for the lower Neckar region in pre-Christian times is also considered unlikely. The assumption that the town’s name comes from the Old High German name Heidilo is now also doubted. Although it is known that the old castle already bore the name Heidelberg (Eberhard von Kumbd calls it castrum Heidelberg), there is no evidence of a presumed landlord named Heidilo from Frankish times.

Sebastian Münsters Heidelberg

Heidelberg is indebted to Sebastian Münster for several illustrations, most of which can be found in his Cosmographia, which contains numerous small woodcuts and a series of double-page illustrations of the city. This includes the large panorama – here in the German edition colored version from 1550 – which is probably the oldest panorama of Heidelberg.

Rudolf Kettemann, Heidelberg im Spiegel seiner ältesten Beschreibung.

1986, p. 28f,

Der Name Heidelberg • The Name Heidelberg

Peter Luder (Latin Petrus Luder; * c. 1415 in Kislau near Mingolsheim in Kraichgau; † 1472) was a German itinerant orator, humanist, physician, and scholar who came from a poor background.

Luder derives the name Heidelberg from the berries of a small plant, blueberries, and traces it to Celtic origins. The reference to the Celts, who still left visible traces in the city area on the Heiligenberg, can hardly be interpreted in any other way than to ascribe “historical age” to the name Heidelberg and thus lend it special splendor. This tendency, repeatedly observed in humanistic historiography, is also evident in Luder’s characterization of the city as “uralt” – urbs antiqua. In any case, attempts by linguists to identify Celtic linguistic heritage in the word Heidelberg must be regarded as having failed.

The derivation of the name Heidelberg from the blueberry can be traced for the first time in Luder and represents the earliest interpretation of the name of the city. A detailed explanation of the name can be found in the work of the humanist and celebrated Latin poet Paulus Schede Melissus (1539-1602), who was entrusted with the management of the Bibliotheca Palatina by Count Palatine Johann Casimir in 1586. In his explanations from 1598, he emphasizes the rich occurrence of blueberries on the mountains near the city and draws on “heather mountains” of other regions as a parallel. At the same time, Melissus reports about a monument on the castle road, a well, on which there were two shields. On one of these shields a mountain overgrown with blueberries and a girl with blueberry bushes in her hand were depicted. In the past, a town flag had also carried the same representation. The town got its name from this “blueberry mountain”.

Luder’s explanation of the name Heidelberg after the berry plant, which was considered characteristic of the city, maintained its place through the centuries alongside various other attempts at interpretation. For the 16th and 17th centuries, in which the etymological interest was particularly awake, on the other hand, the lack of a secure linguistic basis led to outlandish misinterpretations, we should refer, for example, to Sebastian Münster and the explanatory text to Merian’s large city panorama, which is preserved on the Basel copy. In Sebastian Münster’s epoch-making cosmography of the name Heidelberg, we read: “… und wirt somit genent, wie etliche meinen, von den Heidelberen, die darum auff den bergen wachsen”. The author of the text to Merian’s copperplate engraving even quotes the entire passage of Luder about Heidelberg in the German translation of Matthias von Kemnat with explicit reference to “gemeldtes bösen Fritzen gewesener Hof Capellan”.

Since also on the part of the modern linguistics according to the relevant etymological lexicons against the derivation of the name Heidelberg from the blueberries no objections are raised, this interpretation of the name, often discredited as folk etymology, seems to be the most probable. The word Heidelberg would be explained as a parenthesis for “Heidel(beer)berg”, or one would have to assume that “Heidel” was once the name for blueberry in early Middle High German, as is still common today between Lake Constance and Lech.

The spelling of the name Heidelberg has remained relatively constant through the centuries. The variations are essentially limited in the first part of the word to the double vowel (Heidel-, Haidel-, Heydel-, Haydel-), and in the second part of the word to the final consonant (-berch, -berg, -berc). In early times between 1223 and 1308 Heidilberc appears several times, occasionally Heidelburg.

Translated from: Rudolf Kettemann, Heidelberg im Spiegel seiner ältesten Beschreibung. 1986, p. 28f,

Frieder Hepp: Matthaeus Merian in Heidelberg :

Ansichten einer Stadt. – Heidelberg, 1993. p 85

Heidelberg Panorama Von Matthaeus Merian 1620

Heidelberg Panorama Von Matthaeus Merian 1620

In the Styrian Martin Zeiller, who lived from 1589 to 1661, Matthäus Merian found a suitable collaborator who, as a travel writer and geographer, had the best qualifications to supplement and expand the information provided by the engravings as a congenial author. With very few exceptions, the Ulm-based school inspector and book inspector wrote the entire text for the 16 volumes of the “Topography”, which required an extensive study of the sources for each individual city. In keeping with the importance of the time, Heidelberg and its immediate surroundings were honored with several illustrations and described in great detail. Slightly streamlined and orthographically modernized, Zeiller reports the following about Heidelberg:

. ” . . . This town, which is the capital of the Lower Palatinate, lies in the Kraichgau, i.e. still in Swabia. And the Neckar divides the Franks from the Swabians here, so that the Swabians are on this side of the Neckar and the Franks on the other.

Some take the name from the heaths, some from the mountains that surround the town, but most from the blueberries that grow there in large quantities on the Geißberg (“Goats Mountain”) and behind the castle. The town and its surroundings are characterized by fresh, healthy air, as it blows through the Neckar and mountain valleys and is thus purified.

On both sides of the mountains there is wine, in the west and south grain, in the east and north wood, towards the south in the Kraichgau fish in the Neckar and cattle in the surrounding land. . . “

Translated from: Frieder Hepp: Matthaeus Merian in Heidelberg : Ansichten einer Stadt. – Heidelberg, 1993. p. 85