The world’s first filling station

It was in the first days of August 1888. School vacations had just begun in the German state of Baden. At dawn, on Waldhofstraße in Mannheim a large wooden gate opened quietly.. Two boys push a three-wheeled vehicle onto the street. Their mother sits on a leather-covered wooden bench at a crank and steers the vehicle around the first bend. The three of them keep looking back to make sure that no one has noticed. When they are sure that they have not been discovered, Eugen, the older of the two boys, stands behind the cart. With a powerful jerk, he turns the large iron flywheel anchored across the back of the cart — but nothing happens! He rocks the flywheel back and forth a few times and gives it another powerful swing. Meanwhile, Richard, the younger boy, has turned a brass wheel under the seat. “Chug… chug… chug,” responds the large cylinder. The boys jump onto the cart to join their mother. After a strong pull on the lever that moves the flat leather belt from the idler pulley to the drive pulley, the motor car slowly starts to move. Thus began the journey that went down in automotive history!

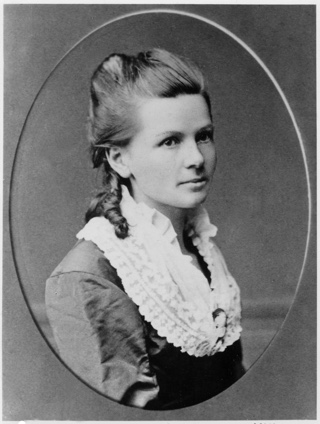

Two years earlier, Dr. Carl Benz, Bertha Benz’s husband and the boys’ father, had invented the automobile in Mannheim, the Benz Patent Motor Car No. 1 (Reich Patent No. 37435 of January 29, 1886) – but no one wanted to buy the automobile. It was only when Bertha Benz, without his knowledge, proved the everyday practicality of the horseless carriage by driving from Mannheim to Pforzheim and back with her 13- and 15-year-old sons that it became a huge success – with almost a billion drivers worldwide today.

Bertha Benz brought mobility to the world, without which modern life on earth would be almost unimaginable. But this great pioneering achievement, which helped the initially ridiculed automobile to finally break through, was in danger of being forgotten.

In Wiesloch, a few kilometers south of Heidelberg, Bertha and her two sons ran out of fuel for the first time. So the three courageous motorists bought a cleaning agent at the pharmacy in Wiesloch that was used as fuel at the time, called ligroin. Thus, the pharmacy in Wiesloch, which can still be viewed from the outside today, became the world’s first gas station.

The three suffered two serious breakdowns on the open road, so they had to repair the car with the “tools of the trade.” Bertha Benz, who was very technically savvy, later described these two rather dramatic situations as follows: “One time, the fuel line was clogged – my hat pin helped. The other time, the ignition broke in two. I repaired it with my garter.”

On the return trip, she had to have the worn brakes repaired due to the constant uphill and downhill driving between Pforzheim and Bauschlott (Neulingen). She later wrote: “I will remember the stretch from Pforzheim to Bauschlott for the rest of my life. In Bauschlott, a cobbler had to nail new leather onto the brake pads after the car had to be pushed several times.“ That cobbler was Karl Britsch, who lived at Pforzheimer Straße 18 and nailed the leather onto the brake pads of her vehicle in front of the ”Adler” inn.

Today, it is hard for us to imagine the difficulties Bertha Benz had to overcome on this first long-distance trip! There were no roads in the modern sense. Out in the countryside, there were only dirt roads, which often had two deep ruts from the wheels of horse-drawn carriages, with the front wheel of the three-wheeled motor car bumping over the turf that had been trampled by the horses’ hooves. The situation was somewhat better in the cities, where the main roads were mostly paved. Driving somewhere today, the computer uses GPS data to show location and distances. Even without a computer, navigation is more easy because roads are well signposted.

What did Bertha Benz find? Nothing! There were no traffic signs! The few local horse-drawn carriage drivers who traveled between the cities knew the route. Passengers in the carriages, on the other hand, were always busy holding on tight, longing for the end of the exhausting journey, and had little orientation through the side windows.

At that time, long distances were already preferably covered by rail. And this was precisely the solution that the intrepid Bertha Benz found: she always drove her automobile along the railroad line, so she couldn’t get lost! Carl Benz had only been able to estimate the fuel consumption of his automobile, as he had only ever driven short distances on paved roads. And he miscalculated enormously, because under such road conditions, the motor car needed so much fuel that it had to be refueled after only a few kilometers. But of course, there were no gas stations yet.

The authentic route taken by Bertha Benz not only connects the almost forgotten original locations of her journey, but also leads through one of Germany’s most beautiful vacation regions, the sun-kissed wine and gourmet region of Baden.

In the Kurpfalz, the area around Heidelberg, you will not only find many well-preserved medieval towns and evidence of Roman times, but also the site where “Homo Heidelbergensis” lived around 600,000 years ago. And since he certainly visited the Heidelberg area from the nearby wall, where his lower jaw was found, he is often referred to as Heidelberg’s first tourist. He certainly settled here because of the favorable climate of the Upper Rhine Plain and the Bergstraße, which has the earliest almond blossoms in Germany.

Heidelberg not only has one of the oldest universities in Europe with many world-famous graduates, it is also the capital of German Romanticism. Visitors from abroad have also always been fascinated by the city and the romantic Neckar Valley. In 1878, ten years before Bertha Benz’s journey, Mark Twain spent three months in the city, and his reports still shape the image of Heidelberg worldwide today (A Tramp Abroad).

The Odenwald offers hikers large areas of forest, wildly romantic gorges, and inviting valleys. The Kraichgau, on the other hand, offers rolling hills, excellent wine, and a rich cultural heritage. Just a few kilometers off the route is Maulbronn Monastery, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, where Hermann Hesse (Steppenwolf) was a student, as were Johannes Kepler and Friedrich Hölderlin.

In Pforzheim, the birthplace of Bertha Benz, the route then reaches the Black Forest, known worldwide for its Black Forest houses, cuckoo clocks, and Black Forest gateau. Those who have eaten too much of the latter can enjoy the huge nature park with its deep forests as hikers; in the evening, a visit to the sophisticated Baden-Baden is a must.

All these landscapes are linked by what makes Baden so incomparable: a Baden food culture that can compete with the best of Alsatian and French cuisine, but also a wine that truly deserves the description “spoiled by the sun”!

If you follow in the footsteps of Bertha Benz, you will discover the magnificent palaces and fairytale castles of Mannheim, Heidelberg, Bruchsal, and Schwetzingen, as well as Pforzheim, the center of the German jewelry and watch industry.